Poet's Statement

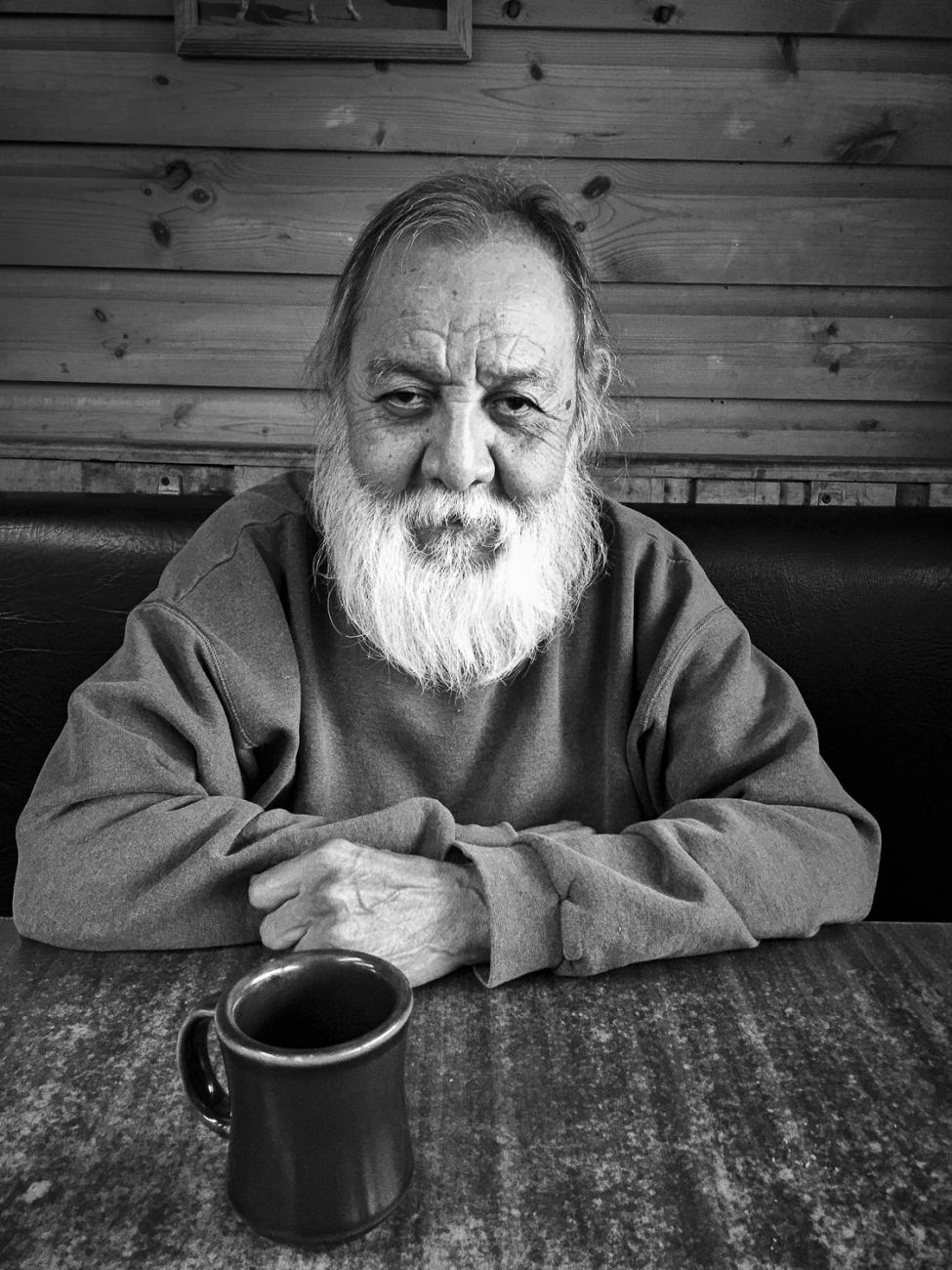

Victor Charlo at His Favorite Cafe, Flathead Reservation, Montana 2015 by Sue Reynolds

Please Note: Victor Charlo’s statement provides a broad overview of how his life has influenced his poetry. As such, it refers to some people and poems that are not included in this resource.

See the poems included in this resource here.

I am a proud father and grandfather, elder of the Confederated Salish and Kootenai Tribes, and Great-great grandson of Chief Charlot, the holdout chief who was forced to lead the last Salish people out of their ancestral homeland in the beautiful Bitterroot Valley in western Montana in 1889, onto the Jocko Reservation, which is now known as the Flathead Reservation.

My name is Chetleh Skyeeme, that means Three Eagles. I was born and raised on the Flathead Reservation and write poems about reservation life, family and friends I love, and have lost, nature, and my journey to visit the polar bears at Churchill, along with other causes I am passionate about, like social justice and the rights of all human beings.

I entered the seminary and studied to be a Jesuit for seven years, but left because it wasn't for me, and I became involved in the early 1960's in Native and social justice causes, most notably The Poor People’s Campaign. Yes, I am a living and breathing civil rights activist from those challenging and turbulent times in American history. Deep down, my writing is motivated by being a rebel WITH a great cause.

I earned degrees from the University of Montana and Gonzaga University. I am also a playwright, and have co-written and produced six plays with my good friend and collaborator, Zan Agzigian, that examine contemporary Native American life. Johnny Arlee, a fellow elder, and I have a theater building at Salish Kootenai College on the Flathead Reservation named after us!

I turned 80 years old in 2018 and live on the old Dixon Agency at the foothills of the National Bison Range.

I am a child of World War II, born in 1938. I lost my brother when I was very young to the Battle at Iwo Jima. My loss deeply affected me. I wasn’t a healthy kid, and nearly died more than once. I had infantile paralysis. The doctors sent me home to die. That’s when I was sent to a medicine man named Jerome, who doctored me once, and I quickly got well.

I was a stutterer. “Wheeeere is my coat?” I would say. They sent me home from the first-grade because of it. I had my new clothes on and all, and yet they still teased me. I recall my father that day exclaiming to me, “Boy, you’re really smart. You finished school in one day.”

Like many other Native American parents of the time, mine didn't teach us Salish, thought it best that I attend White Man’s schools and learn English so I would fit in and not struggle with being different. So I never learned Salish growing up. As a result, my work takes on a sense of loss about the sadness of tribal ways going away. My work reflects on Tradition and the necessity to honor and continue the Old Ways. In one of my poems, Agnes, I write about Agnes Vanderburg, a Salish elder and friend renowned for her knowledge of tribal traditions and her willingness to teach others. In my poem, we are tanning hides and I am learning from Agnes the Salish word for scraper. It is "So hard. So to the point..." The sound of the words in Salish sounded so "to the point."

Living in both worlds made me wonder, why did I even learn to write to begin with? Why did I want to know English? Was it worth the loss of my world going away? Some think of the old ways as going back. I don't. Our lives are not linear; they are cyclical. We always come back to where we are. Now there are younger generations learning the language and that gives me hope. My youngest daughter, April, translated a handful of my poems into Salish a few years ago, as part of my first collection of poetry called Put Sey (Good Enough).

These early experiences are why I write the way I do—with as few words as possible. I cut to the quick. When I write, I try to conjure up the old sayings, those words I grew up with that come out every now and then.

I stopped writing once and realized that writing was all I had to communicate with. Sometimes I feel as though I’m writing about things I’m not supposed to write about, in the traditional sense. There are a lot of things I was told I shouldn’t write about, and I compensate by writing around those things. My poetry tells of the trickiness and difficulty of living in two worlds: Native and non-Native. Through my family, in other elders, in the lives of my children and grandchildren, my good friends, and all of my students, I have been able to discover and foster a continuity and understanding of my life lived in between two worlds via poetry.

Even though these things were hard to write about, they were always surrounded by the Sacred. I always try to walk in a sacred manner, even in my poetry, because writing poetry is a sacred act. It requires me to be as honest as possible with myself about the world around me. I mostly write about things that are Native because that’s what grounds me, things I understand. I don’t try to write about things I don’t understand.

My writing influences are those people who encouraged me along the way: my teachers, writers like Jim Welch and poet Dick Hugo, and my students, when I was a principal, teacher and counselor. While I was studying at the University of Montana in Missoula, I would take Hugo on "driving tours" throughout the Flathead Reservation, where Dick often found sources of inspiration. Hugo dedicated a poem to me called Indian Graves at Jocko, about those times. In my own book, Put Sey, I have a piece titled Letter to Hugo From Dixon. My poetry reflects on a lifetime of memories such as these. When a clever line was said during outings, gatherings or parties where other writers would be, the rule was, you could quickly say, "I'll take that line if you won't..." Many a poem of mine was inspired by this quick ear for the unique or unusual, sharpening my ear, too.

In the Fall of 2001, I left my job at Kicking Horse Job Corps as a counselor, because I suffered a massive stroke. What a life-changing event that made me have to relearn so many basic skills, such as walking, talking, reading and writing! I jokingly but lovingly referred to my setback as "a stroke of luck," because the experience made me more grateful for what I had, a loving family, good friends, and the ability to re-address my writing in new ways, with more intensity than ever before, keener insight, and a graceful wisdom to guide me more towards sharing poetry with younger generations through the Missoula Writers Collaborative. One of my favorite things to do is read to young people in classrooms, libraries, and at special events.

What does all of this mean? What motivates me to write? I have come to find that I live in two worlds, one where you are encouraged to say what’s on your mind and one where you are encouraged to protect what’s on your mind, those things that are sacred to my People’s culture. In the non-Indian world, it seems I can say anything. In the Native world, there are things I can’t talk about or say. So, how do I reflect my world in my poetry telling and not telling my story? That is what I grapple with. My poetry reflects the struggle to define myself while living in these two worlds. I write, “Why did you learn to write?” “Why did you want to? Is it worth the loss of your world going away?” Every time I sit down to write that is what I have to deal with. Are there things that I shouldn’t be saying? Are there things that I shouldn’t be talking about or writing about? How do I still have a voice in the modern world? So, that becomes my fear but it also gives me the courage to push on.

Through reservation imagery, the sounds of my poetry, the symbols, the use of Salish words, I continue to teach myself so I won’t forget. These are the things that I want people to know: you do dig bitterroot, you do tan hides. That is how I was raised. I want people to get a sense of wonder. How did we get here? Is there a trail, a path that we can take so we can do it again? We aren’t always up there at the top of the mountain. Sometimes we are at the bottom of the mountain and you have to figure how to get up.

That is what my poetry is about, how and why I write it, all of this, and a whole lot more.

Victor A Charlo

Dixon, MT

Winter, 2017